|

Leonora O’Reilly (1870 - 1927)

Labor Leader, Trade Union Organizer, Suffragette, Social and Political Activist.

Leonora O'Reilly epitomized the qualities that distinguished the activist women of the gilded age. The child of Irish refugees from the Great Hunger of the mid-1800s, she became an agent of change for the victims of capitalism and imperialism. Forced to leave school at the age of 11 to work in the garment industry, she chafed at the industry's inherent inhumanity and the powerlessness of its female workforce. Through her innate intelligence, self-education, oratorical skills, and forged alliances, she became a renowned advocate for the abolition of child labor, the rights of working women, women's suffrage, racial equality, and the victims of British imperialism in Ireland

Early Years Early Years

Leonora O’Reilly was one of two children born to John O'Reilly and Winifred O’Reilly (nee Rooney) on Feb. 16, 1870 in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City. Her parents were Irish immigrants who fled Ireland to escape the ravages of the Great Hunger that killed over a million of its starving victims and spawned an exodus out of Ireland of another million destitute souls over a period of six years between 1845 and 1851.

Leonora's mother, Winifred Rooney, was born in Co. Sligo, Ireland circa 1841. She came to America in 1847 (Black 47) with her parents. They, like over a million other victims of the Great Hunger, fled Ireland before starvation or death caught up with them. Winifred's father became ill enroute and died shortly after disembarking in New York.

The Lower East Side was the portal to America for many arriving immigrants from the early 1800s to the 1920s. Although a steady stream of Irish immigrants was arriving and living in the Lower East Side since colonial times, the stream crested during the Great Hunger years and did not taper off until the 1850s. Alongside the sprawling tenements that sheltered the new arrivals, factories, shops, churches, and myriad cultural and social organizations abounded. It was in the Lower East Side that Leonora's parents found refuge from the Great Hunger, found work, socialized, met, got married and started a family.

Leonora's father, a printer by trade, died within a year of Leonora's birth. Her brother also died around the same time. Leonora's mother, Winifred, a seamstress, was left alone to care for Leonora without a family member or support system to fall back on. In order to survive, she worked long hours. She was a member of the Knights of Labor, a labor union known for its inclusiveness and ability to organize both skilled and unskilled workers across gender and racial lines in common cause against long hours and subsistence wages. Leonora accompanied her mother to many of the union's meetings in the Great Hall at Cooper Union.

Leonora attended school until the age of 11, when she was obliged to quit and find a job to help her mother make ends meet. Despite her truncated formal education, Leonora continued to self-educate by reading books, newspapers, periodicals, and other materials available at grassroot libraries and social and educational institutions. Many other ethnic-based social and cultural meeting places were also accessible to open-minded and curious individuals like Leonora.

Growing up in the Lower East Side, Leonora was exposed to the best and the worst life had to offer a working-class female teenager in the waning decades of the 19th century. The worst aspects included borderline poverty, sexual harassment, and gender inequality—the mainstays of the male-dominated society that Leonora would battle throughout her life. Some of the best aspects included the creativity, talent, knowledge, and entrepreneurship present amongst the continuous influx of immigrants from Northern and Eastern Europe, many of whom were victims of war and pogroms. Her experiences as the child of immigrants in a melting pot enclave set the stage for her lifelong advocacy of the plight of the downtrodden and marginalized segments of society and, on a different plane, her advocacy of women's suffrage and racial justice.

Child Labor and Early Activism

Leonora's first job on leaving school was in a wig factory. On discovering that she had an unmanageable aversion to handling human hair, she quit. Her next job was in a collar factory where she labored a minimum of 60 hours a week alongside other immigrant children for a pittance. The factories where they worked were filthy fire traps with locked doors and windows. The working conditions were atrocious, akin to prison settings where they were required to work in silence.

From an early age Leonora attended union meetings with her mother. Based on what she learned at the meetings, coupled with her own experiences as a child worker, she became an ardent union supporter who believed that workers had to organize to fight for a living wage, a shorter workweek and better working conditions. In 1886, at the age of 16, Leonora joined the Knights of Labor. The same year, while chairing a meeting in Manhattan to highlight the plight of working women, Leonora met

Josephine Shaw Lowell, a wealthy social and labor activist who had sat in on the meeting. Despite their disparate backgrounds, Leonora and Lowell, together with other women activists, founded the

Working Women’s Society to help women organize, combat sexual harassment, increase wages and shorten working hours. The Society's first activity was to investigate the working conditions for women working in department stores. After the grim results of the investigation were published, the

Consumers League of the City of New York City was founded to pressure employers to improve working conditions and pay fair wages. The Society is still in existence.

One of the colorful characters that Leonora developed a friendship with during her early years attending union meetings with her mother and, later, as a young union activist, was

Victor Drury. Drury was a French-born intellectual, labor leader and political activist who allegedly participated in the revolution that forced the last king of France, Louis Philippe, to abdicate the throne in 1848. After immigrating to the United States in 1867 he became a member of the Knights of Labor where his radical views caused much discord and turmoil within the organization. Their friendship endured through the years and during the latter years of his life he resided with Leonora and her mother in their Brooklyn home.

Leonora's tenacity and quest for knowledge impressed Drury who took it upon himself to help with her political education and critical thinking skills. Drury's own background and life's journey was a window into the world outside of Leonora's own geography that inspired her to expand her knowledge base and intellectual acumen to challenge the economic and political repression of the working poor and the exploitation of women more effectively. In 1888, either through her own volition or at the urging of Drury, Leonora joined the Comte Synthetic Circle that studied the writings of the philosopher

Auguste Comte. On the surface it would seem that subjects discussed within the circle, such as science and philosophy, would be beyond Leonora's ability to comprehend or apply to her work as a labor activist. One aspect of Auguste Comte's treatise that was germane to her work was sociology, the study of human behavior. By all accounts, Leonora's ability to connect to her audience, hold their attention and garner their support for the cause espoused was her greatest virtue.

Labor, Social Justice and Suffrage Activism

In 1894, Louise Perkins, a women’s activist and philanthropist who was aware of Leonora's labor-related and social reform activism, invited Leonora to join the Social Reform Club (SRC). Its membership consisted of men and women, some of whom were well-heeled and learned while others were wage earners and piece workers. The Club's philosophy was loosely based on Tolstoyism, manifested in practical terms by its advocacy of practical initiatives to improve the industrial and social situation in New York for the working classes. In addition to its founder Ernest H. Crosby, the club included prominent individuals from many walks of life, including

Lillian Wald, founder of the

Henry Street Settlement in Lower Manhattan. By the time Leonora joined the SRC, she was an accomplished speaker and a recognized expert on the plight of poor working women and children. As such, she was a sought-after speaker by labor groups and other social reform groups. She was also a featured speaker at the SRC's weekly meetings.

In 1897 O’Reilly organized the local women’s United Garment Workers of America. Louise Perkins, who at that time was associated with the Henry Street Settlement, saw in Leonora an asset in the fight for gender equality and the reform of the social system that disenfranchised women and marginalized the working classes for the benefit of an elitist minority. Fearing that Leonora was jeopardizing her heath by working long hours at her factory job and, during her time off, on union-related issues and on speaking engagements, Perkins and other wealthy activists set up a fund that allowed Leonora to take a year off work to focus on labor and social reform. During that year, she and her mother lived at the Henry Street Settlement where she organized a boys’ club and established and ran an experimental garment workers’ cooperative. Because of the humane working conditions and the quality of clothing the cooperative produced, their pricing was not competitive with the sweatshops, so the experiment ended after a year. What the experience taught Leonora was that she liked teaching and the importance of vocational training for women.

The takeaway for Leonora from that experience was to enroll in the Pratt Institute's domestic arts program in pursuit of a teaching career. She graduated from there in 1900. Lacking the prerequisite academic courses needed for certification to teach in the New York public school system, she took a job as head resident at the Asacog Settlement House in Brooklyn. During her time there, she taught sewing through a program funded by the Alliance Employment Bureau. In 1902 she took up a position at the Manhattan Trade School for Girls as head of the sewing machine operating department. She remained there until 1909.

In 1903, Leonora,

Mary Kenney O’Sullivan, Lillian Wald and Jane Addams were prominent amongst the founding members of the

Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). Leonora served as its vice-president in 1903 and on its executive committee through 1915. She was also a WTUL recruiter and organizer. The WTUL's purpose was to organize women into trade unions and inform the public about exploitative labor conditions. Its membership included working-class, middle-class, and upper-class women of all ethnic backgrounds. The leadership's disparate backgrounds and experiences were oftentimes obstacles that got in the way of effective decision making. Despite such obstacles, the interdependence that underpinned its existence forced its factions to compromise, a testament to its longevity and success. Because of her work in the labor movement trenches and persuasive oratorical skills, Leonora was one of the WTUL's featured speakers, and as such endured an exhaustive speaking schedule for many years.

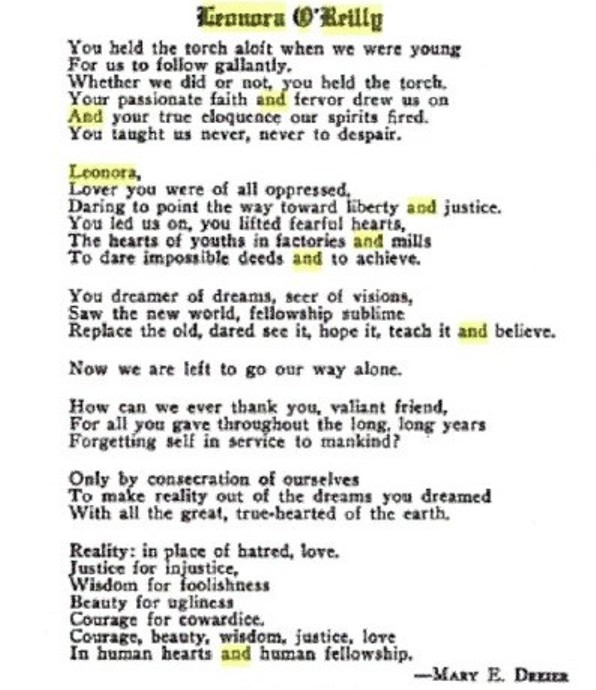

While working at the Asacog Settlement House, Leonora met Mary Dreier and her sister Margaret, both independently wealthy social reformers. As settlement houses were integral to the social reform movement, they were also the venues for benefactors, settlement workers, tenants and associates to socialize and strategize. The Dreier sisters were in search of meaningful work where their education and skills could be utilized effectively. To that end, Leonora had them join the WTUL. Both Mary and her sister remained members for the rest of their active working lives. Mary served as the president of its New York branch from 1906 to 1914. Margaret served as its national president from 1907 to 1922.

Leonora and Mary became lifelong friends. Out of concern for Leonora's health and well-being due to her exhaustive workload, Mary set up a fund to help supplement Leonora's meager income.

Up until 1907, the suffrage movement was within the domain of wealthy and well-connected women who were petitioning for equal rights and access to the ballot box since 1848 without much success. By the turn of the century a new generation of well-educated, socially minded young women, unencumbered by social status and empathetic to the plight of the working poor, became the voice of the suffrage movement. That passing of the torch enabled the suffrage movement to liaise with working women to secure full voting rights for women in New York State in 1917 and nationwide in 1920 by the ratification of the 19th amendment.

At the first WTUL convention in 1907, women's suffrage was incorporated into the lexicon of the labor movement and embraced as part and parcel of the struggle for the abolition of child labor and the exploitation of working women. Leonora and other women labor leaders were well aware that close cooperation between both camps was essential to advance their cause. To that end Leonora and other labor leaders placed emphasis on the enfranchisement of women as an essential element in their struggle for justice and a better life

One of the social reformers that Leonora met and worked with at the WTUL was

Harriot Stanton Blatch. Blatch, unlike her mother Elizabeth Cady Stanton, believed that working women had a crucial role to play in the suffrage movement. To that end and together with Leonora and other labor activists, Blatch founded the

Equality League of Self-Supporting Women (ELSSW) in 1907 to bring working women into the movement. Having secured the participation of working women, Blatch organized a series of suffrage marches in New York from 1908 through 1912. On a cold November night in 1912, a torch march drew 15,000 marchers that was watched by as many as 400,000 New Yorkers. Leonora was always on hand to organize and address the marchers.

Appalled by race riots that broke out in Springfield, Ill. in Aug. 1908, suffragist

Mary White Ovington and other prominent social activists issued a call to convene a national conference on the civil and political rights of people of color. That call was answered by Leonora and a plethora of academics, social and labor activists of all hues, who pledging their support. The ensuing conference that was held in Feb. of 1909 set in motion the founding of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Leonora became a member of the nascent organization and worked with its leadership on issues of commonality, particularly social justice.

In 1909 the

International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union went on strike for better and safer working conditions and a living wage. The strike, which involved mostly Jewish women working in New York's shirtwaist factories, was referred to as the New York Shirtwaist Strike, aka the Uprising of the 20,000. The strike was organized by

Clara Lemlich, supported by the WTUL. As an WTUL executive committee member, Leonora walked the picket lines, raised funds to support the strikers, organized mass rallies and swung public support in favor of the strikers. After three months, the factory owners agreed to a settlement that resulted in increased wages, better working conditions and shorter work hours.

Frustrated by the ELSSW's pivot away from women power to political lobbying to fuel their suffrage campaign, Leonora and other labor activists including

Rose Schneiderman and Clara Lemlich founded the

Wage Earner’s League for Woman Suffrage (WELWS) in March 1911 to provide working women with the means to engage in the struggle for women's suffrage. In addition to the course change by the ELSSW, sexism within the Socialist Party, of which they were members, rendered it impotent in the fight for women's suffrage.

Although the WELWS functioned effectively for a few years, culminating with a sizable meeting of working women at Cooper Union, it nonetheless struggled due to lack of funds. The lessons learned by the ELSSW and the WELWS was that they must work together to achieve equality and women's suffrage. The underlying tension between upper-class women and working women that led to the founding of the WELWS was laid bare by Schneiderman in her "bread-and-roses" speech. The following is an excerpt from that speech.

What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.

On March 25, 1911, within days of the founding of the Wage Earner’s League, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire broke out on the upper floors of the Asch Building located on Washington Place in Manhattan. The fire claimed the lives of 146 immigrants, most of whom were Jewish and Italian workers. In its aftermath, Leonora and Schneiderman, both of whom lost friends in the fire, worked tirelessly organizing protests highlighting the lack of safety standards that resulted in the burning alive of women and children. They also served as volunteer investigators for the investigating commission convened by New York state. In 1912, Leonora testified before the NY State Judiciary Committee with facts regarding the cause of the fire and the utter disregard of the courts for the victims and their dependents.

As a result of the commission's findings, more than thirty workplace fire, safety and health laws were passed and by 1914 a limit was placed on the number of hours women and children could work.

In 1912 the leadership of the WELWS decided to affiliate with the New York State Women's Suffrage Association. In 1914, Leonora and Schneiderman founded the Industrial Section of the Woman Suffrage Party.

On March 13, 1912 Leonora, as a member of a women's suffrage delegation to Washington, DC, testified before both the House and Senate Judiciary Committees in support of a constitutional amendment on suffrage. Her intimate knowledge of the plight of working women and children and her years of dealing with adversarial situations prepared her to confront some of the most powerful men in America, metaphorically speaking, the bane of womankind's existence.

Click here to view her speeches

In 1915, the WTUL selected Leonora to be their delegate to the International Congress of Women, which met at the Hague in Holland to try to find a peaceful alternative to war.

Click her for her report on that event.

In 1919 she again served as the WTUL delegate to the International Congress of Working Women in Washington, DC.

Through to the passing of the 19th amendment in 1920, Leonora maintained a busy speaking schedule for labor rights and for women's suffrage. Her speeches and appeals emphasized the common thread linking child labor, labor rights, civil rights, and human rights to women's suffrage and made clear that without the right to vote for candidates who shared their concerns and values, no meaningful change was possible.

Irish Revolutionary Era Activism

When Leonora got involved in a cause, she was full in. Such was the case during a crucial period in Ireland's struggle for freedom and independence. She was a member of or had some involvement with many of the Irish American political organizations, including Clan na Gael, Friends of Irish Freedom, the Irish Progressive League, and the American Women Pickets that operated in and around New York during that time.

After the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland, the American branch of Cumann na mBan, led by

Dr. Gertrude B. Kelly, undertook a fund-raising campaign in the United States to support the dependents of executed, killed in action and imprisoned Irish Volunteers. Dr. Kelly was assisted by Leonora,

Marguerite Moore and activists from labor and Irish organizations. The overall effort was a success and went a long way in easing the suffering of the Volunteers' dependents. As part of that campaign, Leonora set up an Irish Tea Shop that yielded $7,000 in profit the first year.

In 1917, Dr. Kelly, Leonora, Peter and Helen Golden,

Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Padraic and

Mary Colum,

Liam Mellows and other leading Irish-American activists founded the Irish Progressive League (IPL). At that time, any individual or organization who criticized British policy in Ireland was considered pro-German by the Wilson administration and subject to scrutiny and possible prosecution. The IPL also viewed Clan na Gael, whose members were on the government watch list, too compromised to function as the voice of Irish freedom in America. They believed they could better handle that role.

The first meeting of the American Women Pickets (AWP) for the Enforcement of America’s War Aims was held in New York in April 1920. Leonora was listed amongst the speakers who addressed the meeting. One of the strategies that emerged from that gathering was to draw comparisons to Ireland's struggle for Independence and America's War of Independence. The common enemy was the British Empire and its insatiable appetite for conquest and plunder. By harping on that comparison, Irish activists could counter the Anglo-Saxons' claim that American and British culture were one and the same and that emigrants were destroying that culture.

In the fall of 1920, Leonora founded the Irish Women's Consumer League to boycott British goods. One of the tactics used to highlight the boycott was a reenactment of the Boston Tea Party.

In December of 1920, the AWP and the IPL organized a strike at the Chelsea Pier in Manhattan to protest the arrests of Irish Archbishop Daniel Mannix, an outspoken foe of British rule in Ireland, and Terence MacSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork. Dr. Kelly, Leonora, Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington, and Eileen Curran of the Celtic Players organized a group of women who dressed in white with green capes and carried signs that read: "There Can Be No Peace While British Militarism Rules the World."

The strike, which lasted three and a half weeks, was directed at British ships docked in New York. Striking workers included Irish longshoremen, Italian coal passers, African American longshoremen and workers on a docked British passenger liner. According to a local newspaper report it was "the first purely political strike of workingmen in the history of the United States". Before it ended it had spread to Brooklyn, New Jersey, and Boston. Leonora's reputation and close ties to labor was a key factor in convincing New York dock workers to drop tools and walk out.

Conclusion

By 1919 Leonora, who was suffering from heart disease, was forced to curtail her activities. He exhaustive schedule of work and activism over a period of 30 plus years had taken its toll on her health. By then she was caring for her mother who was aged, frail and in need of constant care. Over her lifetime her mother was her best friend and confidant and her care and comfort was Leonora's primary focus.

In 1907 Leonora had adopted a

young girl

who succumbed to a childhood diseases in 1911.

In 1925, despite her failing health, Leonora presented a yearlong course on labor movement theory at the New School for Social Research.

On Saturday evenings towards the end of her life, Leonora was visited by younger working women and lifelong friends including Pauline Newman, Mary Dreier, and Rose Schneiderman. They discussed labor, politics, and literature, reminisced and shared stories of shared experiences, accomplishments as well as the many remaining challenges facing women and the working poor.

Leonora O'Reilly dedicated her life to improving conditions for those countless millions who, as she had in her early years, labored merely to survive.

Leonora O'Reilly passed away on April 3, 1927.

Contributed by Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

|